All Pain Is Real — Pain And The Alexander Technique

“When you look at some of these things,” Grandner said, “what you find is that the pain is actually only a small part of what is getting in the way of your life. It’s really less about the pain itself and more about the suffering around the pain, and that’s what we can fix.”

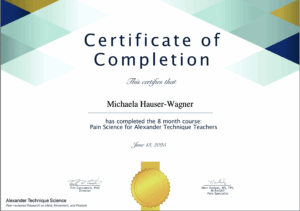

This quote, from an article about the complexities of insomnia in the Atlantic Magazin, captures something important I learned over the past year in a pain science class for Alexander teachers, taught by Tim Cacciatore, PhD, MSTAT and Mari Hodges, M.AmSAT, MScMed: The Alexander Technique can address behaviors and beliefs surrounding the pain and guide people suffering from pain back to mindful movement activities, instilling a renewed trust in the their bodies.

The Alexander Technique (AT) teaches an excellent intervention to deal with the onslaught of stimulation we experience in our daily lives that often involve discomfort and pain: it is called inhibition. Based in neuroscience it is the practice of consciously intercepting/ stopping/ inhibiting the thoughts and sensations that we perceive. It is a process, in which we engage the nervous system with inhibitory messages, in order to interrupt excitation, i.e. doing, anticipating, rushing towards a perceived goal and more.

The Alexander Technique is a “recognized resource for health, productivity, and well-being” (AmSAT mission statement,) aiming for improved functioning of the whole person. Many people who seek lessons with an AT teacher come because of back pain or neck pain, RSI or TMJ problems, as well as headaches. In that respect and historically, the AT has always dealt with discomfort and pain. F.M. Alexander himself was suffering! His hope of becoming an actor and reciter were crushed when he experienced the loss of his voice while performing. After the medical advice to rest his voice for two weeks failed to produce lasting relief, he embarked on a path of self-examination and discovery of what we today would call contributing factors: ‘what am I, the suffering individual, contributing to my problem?’

When F.M. established his teaching practices in Melbourne, Sydney and later in London, cooperation with the medical establishment became essential to make a name for himself. And he did!

When F.M. established his teaching practices in Melbourne, Sydney and later in London, cooperation with the medical establishment became essential to make a name for himself. And he did!

We need to remember that Alexander established his success with students a long time before antibiotics were discovered, let alone broadly available. He was working with people suffering from digestive and circulatory issues, people suffering from the longterm consequences of Polio infection, others who wanted to improve the way they play an instrument without tendonitis pain. And some of them also credited the technique with positive effects on their mood and overall outlook in life.

Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts longer than three months, or pain that persists after the time for tissue healing has passed. By then the nervous system might have created new pathways that increase the perception of pain. One reality of teaching the Alexander Technique is the fact that most people seek our support only, after other treatments have failed. In that respect Alexander teachers might work with students in chronic conditions most of the time.

We feel confident to help them alleviate muscular-skeletal pain caused by tension patterns, overuse, postural and movement issues. But when a young person comes to me two years after a fall and still is afraid of lifting an arm or when another person calls six months after their neck surgery, experiencing tension and pain and unable to turn their head, I see the muscular skeletal problem, but it has clearly turned into a chronic situation.

With students experiencing chronic pain or pain on the threshold of becoming chronic, we need to move differently, slower, with a wider perspective and more emphasis on creating trust and safety, asking for consent, checking in with the client, going slow and taking it easy.

Working on the belief system, educating about pain and introducing gentle guided movement in order to trust again in their bodies are the main areas where the posture and movement teacher can make a difference.

Pain is a protective response to the chance of overdoing an activity, providing a chance for tissue rest and healing. But this natural, protective, evolutionarily advantageous pain response can become overprotective, over-sensitized, hypervigilant, catastrophizing and limiting, thus producing changes in the nervous system.

This table is taken with permission from the above-mentioned pain science class:

| Risky attitude and behavior | Helpful attitude and behavior |

| Passive coping strategies | Active coping strategies |

| Inactivity, avoidance of activity | Engaging in valued activities |

| Resting | Movement, exercise |

| Pushing through | Slow & steady pacing |

| “Freaking out” | Acceptance, understanding |

| Excessive receiving of help | Staying engaged in home tasks |

| Rigid or extreme postures | Variability of posture |

| Pain behaviors (grimacing, sighing) | Creative self-expression |

| Insufficient sleep quality & quantity | Sleep hygiene |

| Smoking | Healthy behaviors, diet |

“It’s really less about the pain itself and more about the suffering around the pain, and that’s what we can fix.” First there must be empathy and then education about the pain, as well as gentle movement with the aim to stay below the pain threshold. Reframing the catastrophizing thoughts and beliefs about the pain on one hand and on the other hand preventing to override current limitations.

Comments

All Pain Is Real — Pain And The Alexander Technique — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>